Case 5:

June’s “Eyes of the Month” case study discusses floaters and flashes and a practical approach to assessment.

Patient Visit:

A 51-year-old man presented to the Queensland Eye and Retina Specialists after waking one morning and noticing significant vision loss in his right eye. Upon questioning he had noticed about a week earlier the onset of new floaters and flashing lights in his right eye when doing some yard work, including heavy lifting of firewood, but thought nothing of it. There was also a patch of darkness in his superior temporal vision, which felt distinctly different to the generalized blur to the rest of his visual field.

His past ocular history was unremarkable. He had not previously undergone any eye surgery and could not remember any instances of ocular trauma. Medical history included hypertension (controlled with oral antihypertensives) and rheumatoid arthritis (managed with Humira, Methotrexate and hydroxychloroquine). He had quit smoking 10 years ago. There was no family history of any ocular disease.

Ocular exam revealed the following:

Unaided Visual Acuity:

RE: 6/30+ (PHNI) LE: LE: 6/7.5++

Intraocular Pressure (IOP):

RE: 13mmHg LE: 14mmHg

Pupils: EA, DCN No RAPD

External examination with slit lamp was within normal limits. No red blood cells were evident in the anterior chamber and there was no iris rubeosis present.

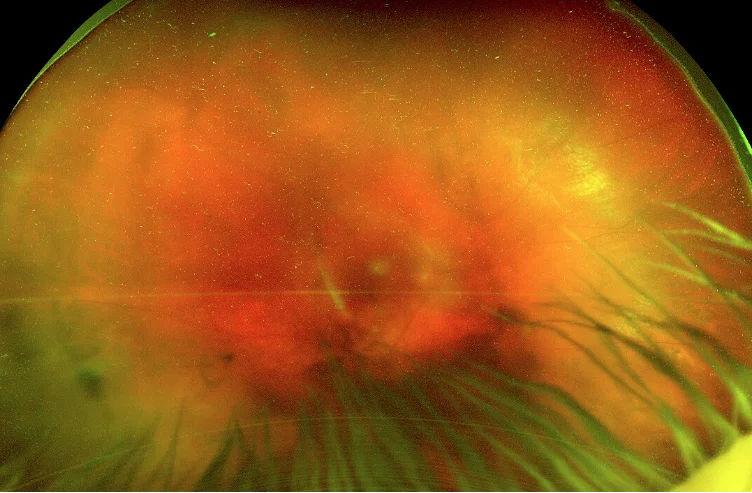

Dilated fundus examination revealed hemorrhage diffusely spread throughout the vitreous. It was not possible to clearly visualize details of the posterior pole (Fig 1). There was potentially an area of retinal tear or detachment in the superior retina.

Figure 1: Optos imaging of the fundus of the right eye.

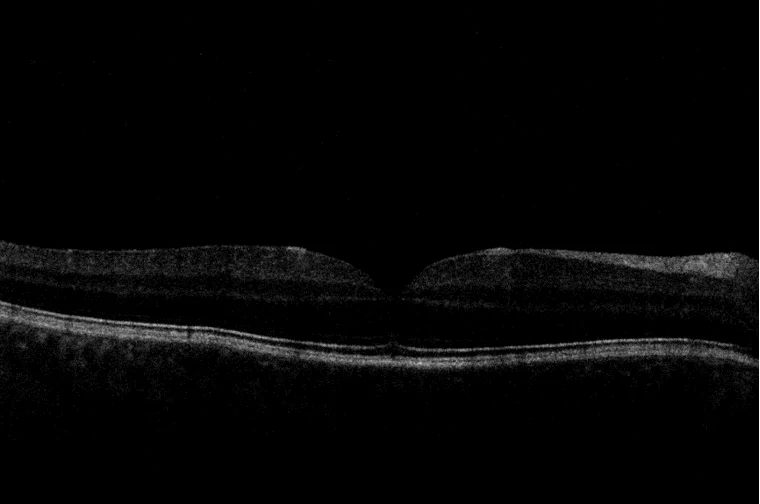

OCT imaging revealed healthy maculae in both eyes, along with established posterior vitreous detachments (PVD) bilaterally (Fig 2).

Figure 2: An OCT scan of the right eye (although low quality due to vitreous haemorrhage), demonstrating separation of the posterior hyaloid from the inner retinal face.

Diagnosis and Discussion

Diagnosis:

Dense haemorrhagic PVD with potential retinal tear or detachment

Differential diagnosis:

PVD with or without retinal tear, with or without rhegmatogenous retinal detachment

Retinovascular (eg proliferative diabetic retinopathy, retinal vein occlusion, macroaneurysm)

Discussion:

Vitreous haemorrhage is a relatively common cause of sudden, painless vision loss, with an incidence of roughly 7 in 100,000. As such, this condition is something optometrists are likely to encounter at some stage in their career. Although vitreous haemorrhage can be diagnosed easily during a dilated fundus exam, the underlying cause is not always immediately evident and always warrants further investigation.

The most common causes for vitreous haemorrhage include proliferative diabetic retinopathy, posterior vitreous detachment (with or without retinal tear) and ocular trauma (which account for roughly 75% of cases). Of particular note, patients with PVD and associated vitreous haemorrhage have a 70% chance of a detachment or tear, versus a 15% chance with PVD alone.

In general, there are two mechanisms which can cause extravasation of blood into the vitreous cavity. The first occurs when there is rupture of normal vessels through mechanical force, such as orbital trauma, penetrating eye injury or PVD associated retinal tear. In these situations, the normal retinal blood vessels can be torn causing blood to collect in the vitreous. The other mechanism is when bleeding occurs from pathological structures. The most common cause of this is proliferative diabetic retinopathy. In this case retinal ischemia prompts neovascularization and these fragile vessels are susceptible to bleeding.

Treatment:

The treatment of vitreous haemorrhage is based primarily on whether or not the underlying cause can be determined. In order to determine the underlying cause, it is necessary to be able to adequately visualize the retina throughout 360 degrees. This is not always possible if there is significant haemorrhage, and thus surgical intervention may be indicated. Bscan ultrasonography can be helpful in identifying significant retinal detachments or breaks.

It is pertinent to remember that although it may be possible to visualize a retinal tear, for example in the above case superiorly, there may be other breaks or detachments hidden by haemorrhage. Also, it may be possible to see a break, but bleeding may prevent adequate tissue uptake of barrier retinal laser. Of note, if a patient is diabetic and presenting with a new vitreous haemorrhage, it is not always safe to assume this is from proliferative changes, as diabetic patients can similarly be affected by retinal tears and detachments.

Treatment in these cases requires pars plana vitrectomy (PPV). When aetiology of the bleeding is unknown, PPV may be both diagnostic and therapeutic.

Case 5 (cont)

For the gentleman mentioned in the case above, it was not possible to adequately visualise the retina. Given the presence of at least one retinal tear, the decision was made to undergo vitrectomy surgery and examine the retina for further breaks. After clearing the haemorrhage, a number of tears (superior and inferior) along with a localised superior retinal detachment were found. Treatment with octafluoropropane (C3F8 gas) and retinal cryotherapy was applied in an attempt to adhere the breaks and detachment.

At his 6-week review appointment visual acuity had improved.

Best Corrected Visual Acuity

RE: -1.00/-0.75 x 180 (6/7.5=)

LE: Plano/-0.50 x 175 (6/6=)

Visual acuity reduction in the right eye was attributed to post-vitrectomy cataract development, the most common complication following vitrectomy. By 1 year almost 50% of phakic patients will develop clinically significant cataract after vitrectomy and as such all phakic patients are counselled on this.

Have any questions about patient eye care?

Contact Queensland Eye & Retina Specialists for more information.

Queensland Eye & Retina Specialists

accepts referrals via email, Oculo, Medical Objects and fax.